Last week, the third issue of Black Mask's crowdfunded benefit anthology, Occupy Comics came out. The comics haven't really been the main event in OC for me as much as Alan Moore's stunning serialized essay on the history of comics, Buster Brown at the Barricades. As good a concise (if hardly neutral) history of comics you will ever read, Moore packs in an extraordinary amount of vividly portrayed historical context into each dense, fiery installment. The final chapters of his essay (written last summer) finally saw print in Occupy 3 and covered the underground comix counterculture of the 1960s all the way through to the present day comic scene. All told, Buster Brown is a fascinating, illuminating and flawed history/opinion of comics told by one of the medium's finest creators.

|

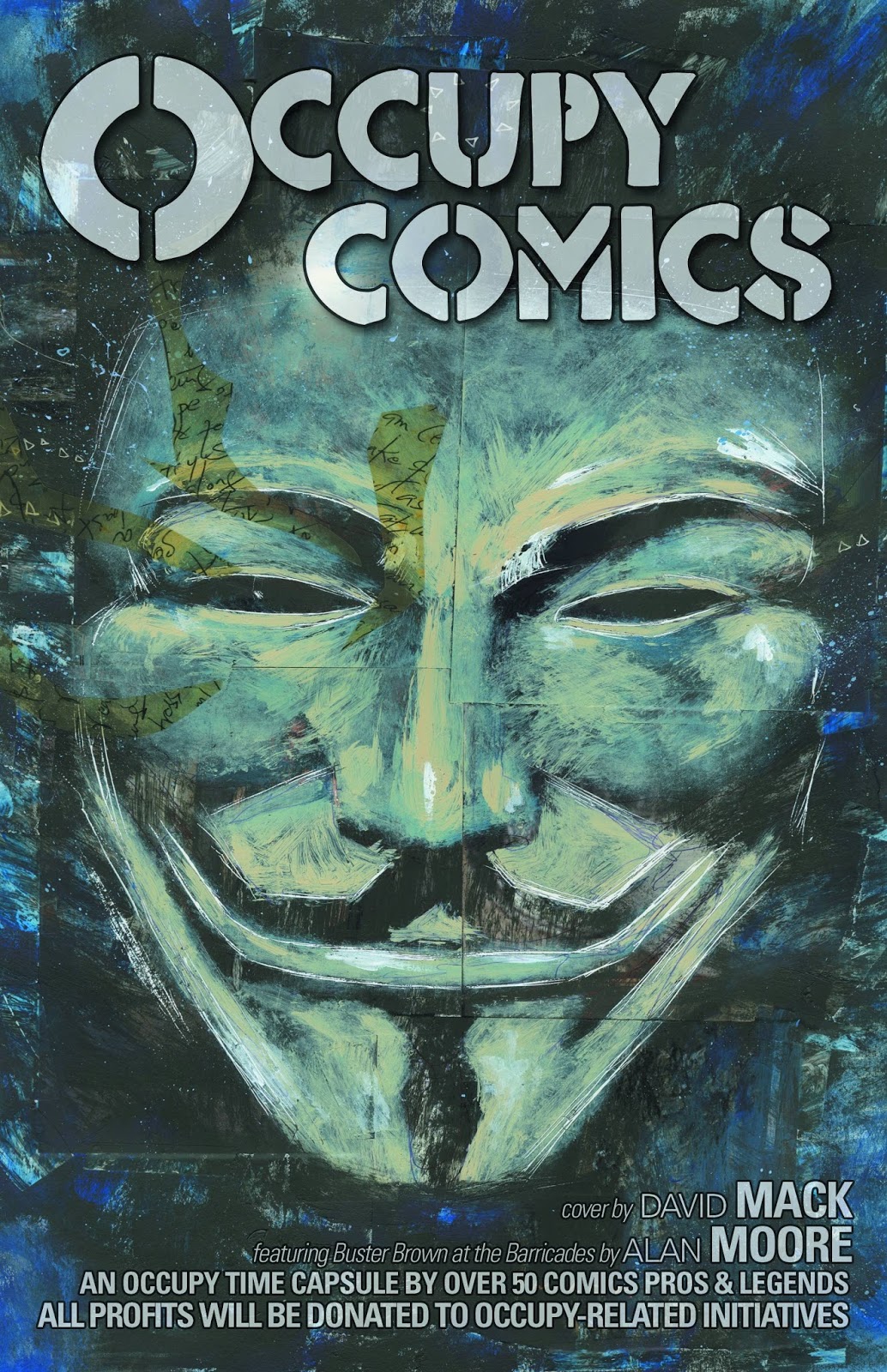

| Buster Brown at the Barricades by Alan Moore, to be collected in Occupy Comics TPB in Nov. |

Most of his essay is solidly mixed with righteous anger over treatment of creators past and present, logical and defensible frustrations with mainstream quality, and a large amount of outright bitterness. He rails against mainstream comics as universally moribund and quality-free. But his passionate rejection of anything remotely mainstream finds him wildly missing the mark in several places. He notes the cutting edge work of Neil Gaiman, Warren Ellis, and Garth Ennis, stating that all three would go on to "relocate to an area of the comics landscape that was as far distant from the mainstream as possible." Which is of course gibberish: all three continue to work solidly within the mainstream American comic market, with all three working for Marvel this year alone. He focuses, appropritately, on both the creative and aesthetic harm Image comics caused the industry during the speculator bubble of the 1990s, only briefly mentioning the company's current "progresive and creator-friendly" place in the market. This is an underestimation and understatement of the company's vital role in a stunning renaissance of critically acclaimed, best-selling, entertaining and high quality creator-owned material being published now.

Moore's narrow view that there is absolutely nothing good in the mainstream wasteland is, of course, spurious bullshit. In Donna Bowman's remarkable series of essays on Breaking Bad for The AV Club, she outlines a similar corollary in television that I think deserves full quoting:

It's easy to look at television, with its 500 channels worth of endless crappy versions of the same empty ideas, and conclude that everything's gone to shit ... [proclaiming] the dreary, inevitable decline of entertainment, and answer my protests to the contrary with assertions that searching for the few worthwhile nuggets in that morass is a pointless waste of their time. Ironically, this pronouncement coincides with the greatest flowering of televised drama and comedy in the medium's history ... the best television ever is on the air right now, in this decade.An identical thing can be said about comics. Moore does point out the many independent works of high quality being produced, and ends on an uplifting note imploring anyone, everyone to create comics. But his blind rejection of anything mainstream, anything popular, writes off truly great material being produced in those arenas. Sturgeon's Law says ninety percent of everything is shit. But that means ten percent is decidedly not. Regardless of the true ratio, the basic tenets of Sturgeon's Law apply regardless of genre and medium. Bowman argues that we are in a golden age of television, and I would argue that in so many ways we are in a true golden age creativity, accessibility, quality and cultural penetration for comics. Moore acknowledges elements of this, but over-focuses on the low quality work in the mainstream. There's nothing wrong with advocating for new, better, different, but there's nothing wrong with the high quality, entertaining and exhilarating works being produced in the mainstream either.

But Alan Moore does absolutely nail it in so many places in his essays, of course. In pieces like Buster Brown in Occupy Comics and his series of enlightening historical essays in Dogem Logic, Moore has shown himself to be a true historian of stunning quality. But that isn't to say his view is perfect or should be taken for granted. When you refine a genre or medium or focus on a particular piece, Sturgeon's Law actually flipflops the ratio, and the bad is outweighed by the good. And in Buster Brown, the good is absolutely pervasive, but still mixed with just a little bit of narrow minded nonsense, not to mention Moore's own blatant whitewashing of his own role contributing to the mainstream he so vehemently rejects.

--

I'll use two cogent sequential passages from Moore's Buster Brown about the 1990s boom-bust but still relevant today to launch into this week's books.

Desperate gimmickry prevailed in limited-edition special-cover efforts to distinguish one book from the next, there being nothing in the content, style or presentation of the work with which to otherwise make such distinctions.Ladies and gentleman, welcome to Villain's Month, DC Comics pointless money grab featuring underprinted lenticular (3D) covers slapped on poorly made soon-to-be thrown out garbage. A month of pointless stories created for the sole purpose of selling fancy covers, a key example of the creative bankruptcy certainly prevalent at DC.

"Crossover events," transparent ploys to make loyal and trusting readership buy every title in the line for fear of missing some important part of a ridiculously sprawling and incomprehensible non-story, would become the major companies' sole strategy for selling their directionless, lacklustre wares.Ladies and gentleman, welcome to Marvel's event-thing, Infinity. I'm sick and tired of events, and the recent track record of Marvel events has been wanting, to be needlessly generous. But I've been enjoying Infinity, crafted by one of modern mainstream comics truly new and unique visionary talents in Jonathan Hickman. There are certainly pointless tie-ins meant to suck up dollars, but I believe the comic audience is bright enough to know what these are and skip them. The necessary bits of Infinity, hardly a non-story but certainly arguably incomprehensible to the uninitiated, aren't quite as sprawling as events past. So what about this week's Infinity 2? It was a decent, entertaining middle chapter, gorgeously illustrated by the amazing Dustin Weaver and Jerome Opena with a slightly silly twist at the end, sure, but you sure get your bang for your buck with this series.

Not to be outdone with just one crossover, oh no!, Marvel also put out the first two chapters of Battle of the Atom by the consistently inconsistent Brian Michael Bendis and the consistently awesome Frank Cho and Stuart Immonen. This is one of those old-timey X-book-x-overs that sprawls across a bunch of different titles and creative teams (see my breakdowns of crossover types from last week), these chapters in a one-shot and All-New X-Men. Bendis only falls into his usual verbal traps in the second part but thankfully we've got Cho and Immonen to make it shine. The story is surprisingly straight-forward (things are TOO timey-wimey so that has to be stopped ASAP) and I loved the nice little twists in the future X-Men team (Princess Power!). I tend to dislike Time Travel nonsense so hopefully this wraps up all those stories. Hopefully.

It was a pretty light week, but there were a couple of good releases worth noting: Satellite Sam 3 by Fraction & Chaykin was superb, Trillium 2 by Jeff Lemire was as beautifully drawn and compelling as the first issue, Daredevil Dark Nights 4 by David Lapham was weird and entertaining, and Superior Spider-Man 17 was gimmicky, sure, but I've been digging this whole run, so what the hell.

And of course a must-own, Love and Rockets: The Covers finally came out, and it was most definitely worth the wait. (By the way, if you haven't had a chance, check out my Definitive Love and Rockets Guide!) Happy Wednesday, everyone!

No comments:

Post a Comment