|

| Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future by Fred Hampson |

Exploring the Dan Dare Comics of Grant Morrison and Garth Ennis

There was a nice little Easter Egg of sorts in a recent issue of Jonathan Hickman's

Avengers, as part of a series of one shots focusing on the origins of various updated or multiversally-transplanted characters joining a new, globally expanded Avengers lineup. One of these characters is the new "Smasher." A couple of years prior, college-age astronomy student Izzy finds a pair of space-goggles on her family farm in Iowa and through a small series of cosmic misadventures finds herself the first human admitted into the Shi'ar Imperial Guard. Upon returning to Earth, her elderly grandfather gives her the card of an old World War II buddy, Steve Rogers, encouraging her to join the Avengers. She is accepted and it is revealed that her full name is Isabella Dare; the card from her grandfather, signed Dan.

This is of course a sly reference to Dan Dare, the great 1950s British sci-fi comic book hero. Created by Frank Hampson for the seminal

Eagle anthology magazine,

Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future featured the titular Dare and associates in their space-bound adventures. It would be a bit reductive to call it England's Buck Rogers, but Dan Dare certainly shares in the legacy of male space action heroes that populated the popular imagination of the era on both sides of the Atlantic. Very, very British, Dan Dare shares as much of his legacy with the youth adventure books of the era focusing on pilots in the Second World War as with any contemporary science fiction work. The strip's early efforts by Hampson featured complex, long serialized storylines. Over time Hampson would be forced off the title and it floundered in the 1960s, seeing brief revivals in the 1970s in

2000 AD and a long, heavily retconned run in the revitalized

Eagle in the 1980s, both pale shades of the creative and artistic heights achieved under Hampson's watch.

Dan Dare's adventures play an important role in the unique tradition and history of comics in England, although he has been largely absent in recent decades. Many of the important British writers and illustrators who contributed to the tidal wave of talent flowing into the U.S. from the U.K. in the 1980s were influenced heavily by Dare's pulpy, slightly anachronistic adventures. Indeed, an entire generation of Britons would fall under the influence of the strip's quintessentially British space heroics. Two such writers were Scottish scribe Grant Morrison and (to a different extent) the Northern Irish Garth Ennis, visionary creators with absolutely nothing in common, with the notable exception that each writer has helped produce startlingly original works based on Dan Dare. And unsurprisingly, each creator's work with the character reflects his own long-established, fiercely unique (and diamtrically opposed) aesthetic.

(It's important to point out here that both works utilize boldly reimagined versions of the established Dan Dare cast and setting. Perhaps "reimagined" isn't quite what Morrison and Ennis did as much rethought within the context of time passed. These are not ill-planned modernizations like the 1970s

2000 AD work, but sequels, dark mirrors of the glorious past, in each instance a new reality extrapolated into a future Dan Dare did not fight for, but achieved nonetheless. It is not any more necessary to have read the original 1950s comics to understand who's who and what's what any more than it is to have read the Silver Age to understand any modern superhero, or perhaps, to have read

Astro Boy to understand

Pluto.)

Dare by Morrison and Hughes

|

Dare, by Morrison and Hughes

(Fleetway, 1991/Fantagraphics, 1992) |

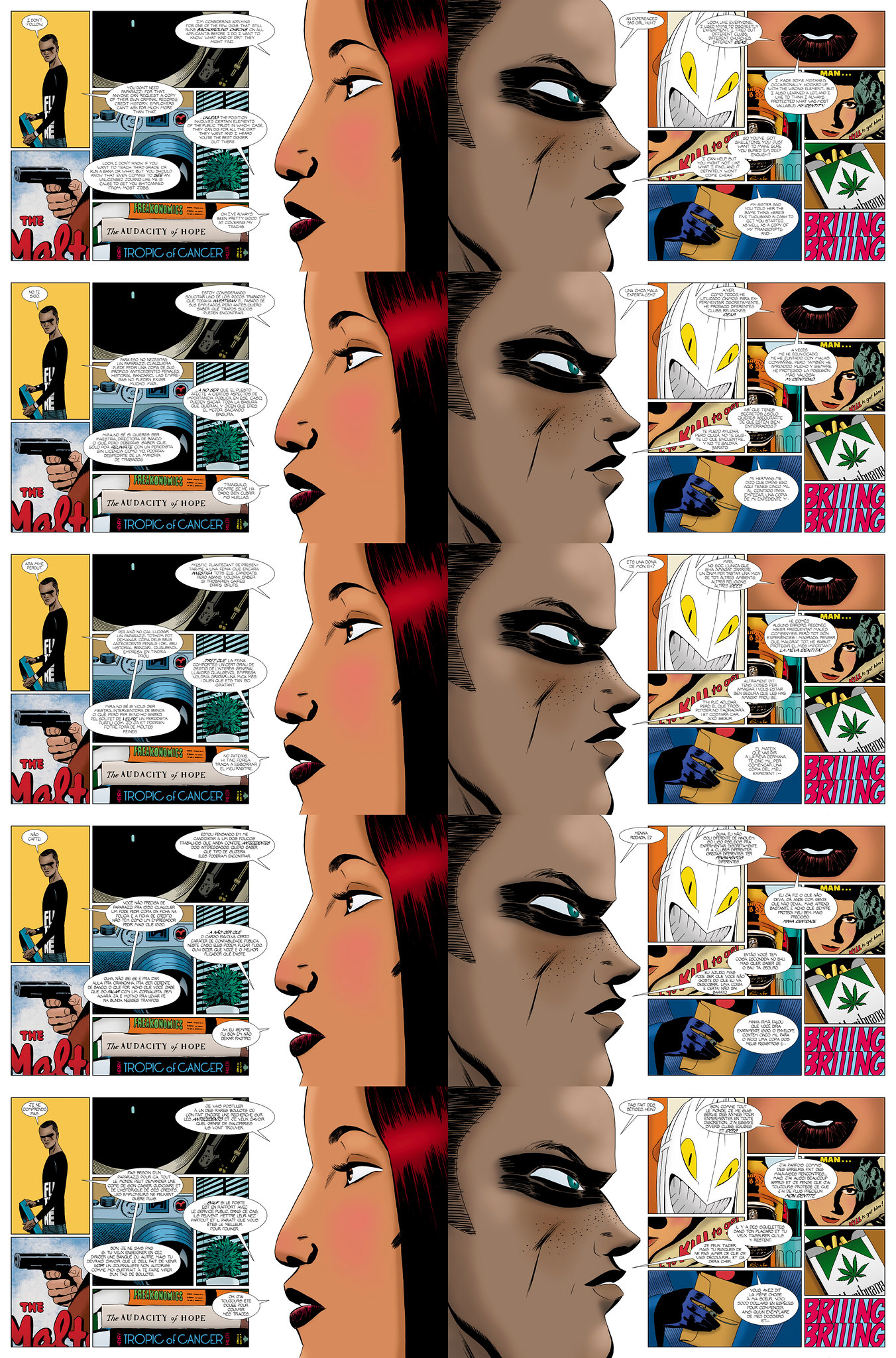

The first of the two writers to tackle the legacy of Dan Dare was Grant Morrison, in concert with artist Rian Hughes in a story serialized in the short-lived

2000 AD spinoff

Revolver in 1990. What Morrison and Hughes accomplish with

Dare is frankly nothing short of astonishing, even more surprising that Dan Dare's rights-holders allowed Morrison carte blanche to tell a story as subversive and dark as he did. Not only are the themes presented a transparent satire of the destructive social policies of Margeret Thatcher in the UK in the late 1980s (as well as politics and media in general), but a fierce and stinging commentary on the tragedy that was the life of Dan Dare's creator Frank Hampson.

The Original Sin of American Comics was, of course, the purchase of Superman from Joe Siegel and Jerry Shuster for a pittance, and their subsequent mistreatment and rejection by the multibillion dollar company and industry their creation helped forge. This is referred to as the Original Sin, less for the Christian biblical parallels - Siegel and Shuster and their creative descendents aren't the ones living in perpetual sin for their actions, but the first victims of a particular strain of corporate greed that echoes down generations. It set a standard of a form of creative robbery that devalued the comic creator in a way not seen in other media, a trend that has only recently seen any kind of mitigation. For British Comics, with its unique trajectory rooted less in superhero comics and more in sci-fi comic anthology magazines, Frank Hampson's treatment by his employers at

Eagle, though not as bad initially as Siegel and Shuster's treatment by National, still left Hampson penniless, suicidal, and eventually dead, an almost forgotten figure.

Morrison and Hughes'

Dare reflects the tragedy of Frank Hampson in almost a roundabout way for much of the story, the tragedy's influence only being made crystal clear at the very end. But even absent the Hampson parallels,

Dare is a brilliant work of postmodern science fiction. The story opens with Dan Dare, retired, living out his life in solitude on his estate, hobbled by age, plugging away at memoirs he will never finish. His past glories are long gone, the friendships from his past just another dusty memory. Jocelyn Peabody, his could-have-been paramour from his adventuring days is dead, by apparent suicide. His one-time best friend and right-hand man, Albert Digby, won't even look him in the eye at the funeral.

The Prime Minister, Gloria Monday, shows up, not to pay her respects but to recruit Dare. There's an election on, and Monday's Unity Party needs a symbol for the masses, an agreeable and positive representative to tip the balance. With few other options, Dare agrees to become a propaganda tool for the Unity party. He is indifferent to the politics, but this gives him a chance to relive past glories, and he needs the money. After doing some campaign work, Dare is approached by a mysterious agent of Digby's. She flies him to a secret location, touring the wasteland that has become England along the way. Things are rosy in the South, but the North continues to show the scars of Monday's destructive socioeconomic policies. The food lines last days, the free Treens - the alien species native to Venus who once were the subjects of the genius dictator The Mekon - live in retched ghettos, the past architecture of the future rotting away like a corpse in the sun. Digby is seeking out Dare because Peabody's death was no suicide - she knew too much, involved in a conspiracy that reaches all the way to the Prime Minister.

We learn the source of Digby's antipathy to Dare. After the fall of The Mekon, the Treens became subjects of Earth, Venus nothing more than a source of food for the increasingly starving and impoverished human population. The Treens rose up and the military, at the direction of the Unity Party, brutally puts down the rebellion, killing scores of innocent civilians in the process. And Dare was front and center of the atrocities, not that Digby is innocent either. It was war, and war can be unspeakably ugly. Digby convinces Dare to join him in finding out what Peabody knew, and the revelations force Dare's hand in taking action against Monday, herself just a tool of the returned Mekon.

The Mekon was Dare's greatest foe, one of the smartest beings in the solar system. And Mekon's machinations have proved fruitful. He's won, plain and simple, and on the surface there's not much Dare can do about it. The end, though, comes in fire, a complete wiping of the board, a mutually assured destruction, the final act of a desperate, broken man against an intractable enemy and against a future he helped create.

Rian Hughes' art in

Dare is nothing short of revelatory. Hughes, one of the most distinctive visual voices in comics, could not have been a better choice for the project. Hughes' heavily designed and pop-fifties-infused style was the perfect visual commentary to match Morrison's postmodern narrative. In the original stories by Hampson, the visual (and narrative) aesthetic was one of gee-wiz sleek fifties-futurama projected into the future. Hughes' art reflects that, showing a future both anachronistically inhabiting the surface promise of that era and existing among the wreckage of the decaying past, the crumbling infrastructure a larger symbol of England's rotting soul.

Morrison is now someone who has a legacy of work that embraces the better angels of our nature, celebrates the possible and revels in genre. But

Dare possibly represents Grant Morrison's most cynical work, both in the political commentary and his own views of Dan Dare's place in popular culture. In the effects on England and the costs of using Dan Dare as a tool of political war crime, his anger at Margaret Thatcher and her policies oozes out of the story, about as subtle as Urasawa's anger at George W. Bush in

Pluto. Monday is willing to do anything for power, including making a deal with a genocidal dictator. And as part of her (and The Mekon's) plan, she utilizes Dare as a symbol to maintain power, a once honorable man corrupted completely. And Morrison's intent here just isn't Monday's use of Dare, but the continued use of Dan Dare as a property in the real world, an archaic symbol brought up and pranced around at the benefit of people who had no hand in creating him. The final powerful pages fade from nuclear-white to pull away and show a blank art board sitting on a table, pure MetaMorrison. The book closes with a quote, from Hampson himself: "Although I wished he would, Dan Dare refuses to lie down and die..." The message that Dare's exploitation is reprehensible. Naturally Morrison himself is a party to that continued travesty, if it is indeed such at all.

Dan Dare by Garth Ennis and Gary Erskine

In 2007, Virgin Comics - a publishing concern predicated on putting out works

by Indian creators with an eye on tapping into the largely

underrepresented comic market in one of the world's largest countries - got the Dan Dare license and hired writer Garth Ennis and artist Gary Erskine to tackle it. An inspired creative decision from an odd choice of publisher, but the finished work is truly remarkable.

Now, I'm very familiar with both Grant Morrison and Garth Ennis's deep libraries, and it's hard to imagine two more diametrically opposed aesthetics. Morrison loves the superhero genre, Ennis abhors it. Ennis has a produced a large amount of straightforward historical dramas, Morrison revels in metafiction. Ennis is known for the sublime ridiculousness of his extremely dark

humor, Morrison embraces the lighthearted ridiculousness of genre. Indeed, Ennis is not especially well known for his popular genre work - while he has worked within superhero universes in a few limited examples, those comics were hardly superhero books themselves, and his one notable superhero opus

The Boys is especially marked by his dislike of that genre. Many of his other (non historical fiction) works may have some fantasy or science fiction element, but those elements are hardly the focus. That is why I was genuinely surprised to see Ennis tackling Dan Dare, a most unambiguous science fiction property. He notes in his excellent introduction - and there is no better writer of introductions or forwards remotely involved in comics today - that his frame of reference for Dan Dare is not rooted in nostalgia for the original works, and his goals with the project were decidedly distinct from what any other writer has attempted with the property. And what Ennis pulls off in his Dan Dare is nothing short of remarkable in a career built on consistently remarkable works.

The best works of Ennis's long career are his war comics, not just shoot-em-up genre fap but genuine character oriented historical dramas told with respect for the people and history of the time, and with just a tinge of his trademark black humor. Ennis is a student of history, and his war comics, packed with technical and historical detail with an eye on the sacrifice made by very real people, are singularly remarkable in the comics field. No-one else working in comics can pull of what he consistently does with his war comics. And his

Dan Dare, more than anything else, is a war comic, told with the same level of attention to detail and respect for character that he brings to his historical fiction. To approach Ennis's

Dan Dare like his historical dramas is not to reject its sci-fi adventure nature. Indeed, Ennis embraces the genre and utilizes the tropes of the genre while at the same time completely turning every single one of these tropes on their head.

Like Morrison's

Dare,

Ennis's Dan Dare opens with Dare in his retirement, living among artifacts of his past in complete solitude. The future that he fought for is not the future that he finds himself living in. The Mekon and his forces were exiled from the solar system and some modicum of peace was achieved on Earth, with Britain at the forefront of technological and military advancement. But War broke out on Earth - China and the United States are burned out husks following a brutal and, apparently complete nuclear war. What is left of Earth exists at the whim of Britain's technological and financial generosity. And the corruption of power worms its way to the top. Dare was approached by xenophobic elements in the British government to be the face of their party, and he rejected them, choosing to live in peace on an asteroid, completely separated from Earth.

Envoys from the Prime Minister approach Dare asking him to come back into service. It appears The Mekon's forces are re-entering the solar system and his services may be needed. Dare sees through the message to the core of what's happening, that he'll be used as a prop. But there is genuine need - as he is being pitched the temporary return to service, most of the British space forces are ambushed at the edge of the solar sytsem and completely routed by The Mekon's forces. Dare, above everything else, believes in Britain and Earth and will serve because that is his duty. He meets up with his old friend Digby, and gets into contact with his old paramour Peabody, who is now Home Secretary under the PM. Not dragging things out, Ennis rips the bandaid off the conspiracy quickly - Peabody finds out the Prime Minister is in league with The Mekon, and quickly acts to take control of the government. Things happen fast and furious and the action that ensues Earthside is a damn fine political drama. Back in space, after a setpiece that may as well be a treatise on military strategy, Dare takes control of what is left of the British space forces and sets out to confront The Mekon directly.

It is the pure Britishness of this

Dan Dare that adds to this work's remarkability. Dan Dare's service is rooted in his grand belief in Britain above all else. He is an honorable man who will fight for his country over and over, regardless of the circumstance. There are many recurring themes in Ennis's war comics. One of them is the soldier's duty in contrast to the soldier's accomplishment. Often Ennis makes note that the end result of the soldier's sacrifice may not be what the soldier sought out to do, the future achieved not what the soldier fought for.

Dan Dare is no different. Dare fought for Britain only to see them abdicate their responsibility in the aftermath of the U.S.-China nuclear war, taking advantage of the remnants of the world rather than taking leadership. But he fights now because this is his duty. As Peabody notes, "He saved us again and again, and what do we do? He blazed the trail and we paved it with excrement. But he'll fight for us now, because he loves this country more than life itself."

The sacrifices made in defense of country and planet are not taken lightly, the soldiers who die not base redshirts thrown into the cannons, but human lives lost in the line of duty. Dare, as commander of the forces, knows and acknowledges that the price of freedom is blood and every loss is felt. At one point a major character falls in battle, sacrificing himself to allow ships of civilians escape from The Mekon's forces. It is a heart-wrenching moment, seemingly representative of every such sacrifice made in the history of warfare. Ennis is someone with the uncanny ability to make war comics that don't glorify war and that don't preach. There is a larger message, of course, but it is not about the nature of war. It is, in essence, about embracing British exceptionalism, more specifically about rejecting the imperialistic exceptionalism that breeds greed at the expense of the third world and embracing the exceptionalism that says Britain is in a unique position to benefit the galaxy (world) through leadership and acts of goodness and inclusion.

And on top of all this, Ennis and Erskine's

Dan Dare is a consistently exciting work of science fiction that plays with the expectations of genre and story. This may be a future sci-fi story, but the uniforms of the military, the equipment they use, even the tactics of the ships in battle are all very recognizably modern, which is important. Where Hampson's work (and by extension, Hughes' art in

Dare) was a projection of 1950s sensibilities into a gee wiz future, Erskine's art and Ennis's story is very much a projection of not just the now but the constants of military functionalism into an accessible futurescape. The result is a logical, accessible, entertaining. And storywise, no major or minor character is safe from the consequences of warfare. People die in war, that is the brutal reality of it. Just because Ennis spent seven issues setting up a character to have a genuine, transformative arc doesn't make them safe from the consequences of war. Everywhere where you think the story will zig, it zags. Built on a foundation of logic, it notes the silliness inherent in sci-fi, embraces it and then brushes it aside. We get a perfunctory technobabble explanation of The Mekon's grand weapon, which Dare simply brushes off. There is a mission on, and the nitty gritty details just get in the way. And unlike most science fiction of the 1950s, there is a very strong female presence in the characters of Peabody and Lt. Christian, a young officer vaulted into command because Dare sees the potential in her.

Where Morrison's

Dare was cynical and a bit hamfisted in its political message, Ennis's

Dan Dare is accessible, riveting, entertaining, subtle and hopeful. Both works fulfill the promise of science fiction to comment on society and humanity, becoming so much more than a human vs alien shoot-em-up (though Ennis's manages to have more than its share of that, too). And both works pay homage to the original works that so influenced a generation of readers while breaking free and telling their own unique stories, transcending and embracing genre in equal measure.

--

Dare by Morrison and Hughes was serialized in

Revolver magazine in 1990 and 1991 and collected by Fleetway shortly after, and reprinted in the United States in 1992 as a mini-series by Fantagraphics as

Dare: The Controversial Memoir of Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future. It is currently available collected in the indispensable

Rian Hughes anthology Yesterday's Tomorrows, from Image.

Dan Dare by Ennis and Erskine was serialized by Virgin comics before the company folded. Dynamite Entertainment bought the license and released the material in hardcover and softcover as

Dan Dare: Omnibus Volume 1. The Frank Hampson material is sadly out of print.